Press gangs in Portsmouth

Press gangs as a Royal Navy recruitment method played a crucial role in British naval history, particularly during the 17th and 18th centuries when maintaining a powerful navy was essential for national defence and empire expansion. Press gangs were groups authorized to forcibly recruit men into naval service, often targeting sailors, laborers, and others with maritime skills. These recruitment practices were often controversial and sometimes brutal, raising tension in coastal communities where men lived in fear of being seized for service.

Alongside press gangs, the Royal Navy employed a variety of recruitment tactics, from offering enlistment bounties to the "Quota System" where towns had to supply a certain number of men. This page delves into the history, methods, and impact of these recruitment practices, illustrating how they shaped both naval power and British society during an era of intense maritime competition.

The practice of impressment (also known as Shanghai-ing or crimping) was common in all the world's ports until about 1820, and was widely used by Britain's Royal Navy as a means to maintain crew numbers on its warships.

Recruiting sailors purely voluntarily was difficult as the conditions on board ship were poor and serving in the navy, especially at times of war, was very dangerous.

The word press gangs derives from the term impressment, which can be defined as, the act of coercing someone into government service. Impressment was used from as early as Elizabethan times and was last used during the Napoleonic wars 1803-1815.

The press gang, a group of 10 - 12 men, led by an officer, would roam the streets looking for likely 'volunteers', merchant seamen were particularly prized as they already had seagoing experience and needed less training.

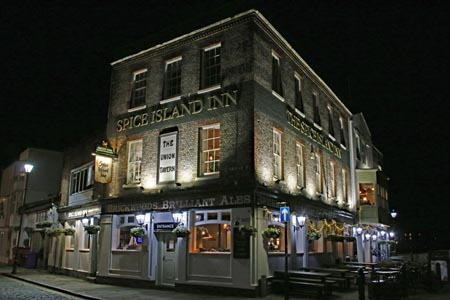

The area of Spice Island, in Old Portsmouth, seems to have been a favourite recruiting area due to the large number of pubs, hostelries and other establishments that existed there.

Certain groups were exempt from the impressment process, apprentices were exempt. Officially foreigners could not be impressed, although they could be persuaded to volunteer and there was an age limit 18 to 55 years. But the rules were often ignored so that the press gang could earn their reward, they were paid by the head.

Often men were knocked unconscious or threatened and often violent fights broke out as groups tried to prevent friends or work mates being impressed into service.

Impressment was legalised during the reign of Queen Elizabeth, but had been in common practice as far back as the 13th century for the recruitment of soldiers. Queen Elizabeth passed an act in 1563 laying out the use of sailors forced to join the Royal navy. In 1597 a further act allowed vagrants to be forced into naval service.

Sometimes when there was a greater need for seamen the Government offered a bounty for volunteers ranging from £2 to £5 and sometimes large towns offered bounties. In 1803 Portsmouth Corporation offered a sum of £100 to the first 100 seamen to join up in the port. But even with the payment of bounties to volunteers to join up, the numbers of men joining up was not enough and the practice of impressment continued.

When the press gang had seized a man, he was offered the King's shilling as a reward for volunteering, but often the coin was issued in devious and underhand ways, such as slipping the shilling into a pocket, or dropping it into his drink. If you were in possession of the shilling then that was good enough for the press gang. It is for this reason that glass bottomed tankards became popular, so that you could check your drink didn't contain a shilling before drinking it.

Not surprisingly corruption was rife, many wealthier men escaped impressment by simply bribing the press gang, other men would play the dangerous game of taking the King's shilling and then running away and repeating the act elsewhere.

It was common practice for impressed men to find substitutes for themselves, prove that they were unfit to serve or prove that they already had respectable employment. There was an agency based in Hawke Street, Portsea, that supplied at a price substitutes to take the place of pressed men. For the cost of 10 guineas the agency would supply a substitute thus freeing the pressed man.

Often impressment took place at sea where press gangs would board merchant ships with captured sailors being pressed into service, leaving the merchant vessel dangerously under manned to continue on its journey.

New laws were enacted in 1835 reaffirmed that impressment to the Royal Navy was a legal practice, but limiting the length of service to 5 years and limiting stating that a man could only be pressed into service once.

After 1853 the need for press gangs diminished, at this time the navy introduced continuous service for sailors with a more structured career and a pension on retirement, this led to more men joining on a voluntary basis and reduced the need for impressment.

The Royal Navy grew from 270 ships in 1700 to about 500 in 1793 and almost 950 vessels in 1805. The larger size fleet required more seamen. The use of the press gang in Portsmouth seems to have peaked at around 1803 at the height of the Napoleonic War. In peacetime the numbers were much less than in today's Navy and varied from 12,000 to 20,000 men during the Eighteenth Century. In wartime, strength increased from 40,000 in the Wars of 1739-1748, to 150,000 at the peak of the Napoleonic Wars.